『{英語、数学、国語、家庭科、others}なんて、何の役にも立たない』と思っている子ども(学生)に対して勉強をさせることは、この「もっとも辛い懲役」と本質的に同じではないか、と私は思うのです。

世の中で最も辛い懲役(懲罰的役務)と言われているものは、

The harshest punishment (penal labor) in the world is said to be,

―― 今日、地面に穴を掘らせて、次の日に、その穴を埋めさせる、という作業を毎日続けさせること

forcing someone to dig a hole in the ground today and fill it up the next day, repeating this task endlessly.

とされています。

So it is said.

これは「意味のない作業を延々と強制されること」が、人間にとって極めて大きな苦痛になるからです。

This is because being forced to carry out meaningless work endlessly inflicts immense suffering on humans.

地面に穴を掘る作業そのものは、肉体的にきついものの、もしそれが「農業のための準備」や「建物の基礎工事」といった目的を持っていれば、人は耐えることができます。

Digging a hole itself is physically demanding, but if it serves a purpose? Like preparing for farming or laying the foundation of a building? People can endure it.

目的があることで、苦労の中に価値や達成感を見いだせるからです。

Because with a purpose, one can find value and a sense of achievement in hardship.

しかし、今日掘った穴を明日には埋め戻すという行為には、一切の成果も残らず、意味も見出せません。

However, filling in the hole you dug yesterday leaves no result, no meaning to be found.

この「無意味さの強制」が人間の精神を消耗させ、どれだけ体力があっても心を折ってしまうのです。

This enforced “meaninglessness” exhausts the human spirit and breaks the will, regardless of one's physical strength.

要するに、最も辛い懲役とは、肉体的な苦痛そのものではなく、「無意味な労働を強制され続けること」による精神的な拷問なのです。

In short, the harshest punishment is not physical pain itself but the mental torture of being forced into meaningless labor continuously.

『{英語、数学、国語、家庭科、others}なんて、何の役にも立たない』と思っている子ども(学生)に対して勉強をさせることは、この「もっとも辛い懲役」と本質的に同じではないか、と私は思うのです。

Making children (students) study subjects they believe are “useless, like English, math, Japanese, home economics, etc.” is, in essence, the same as this “harshest punishment.”

もちろん、これらの勉強は“受験合格”という目的のためには意義があります。

Of course, these studies have meaning when tied to the goal of passing entrance exams.

しかしこれは「目的」そのものではなく、「合格という手段」としての作業です。

But this is not a true “purpose” in itself, only a means to the end of passing.

そして一度その目的を達成すれば(例:受験に合格すれば)、その勉強の意義は消え、学びから離れていくことは自然の流れです。

And once that purpose is achieved (e.g., passing the exam), the study loses its meaning, and leaving it behind is only natural.

この懲役に対抗できる人間は二種類いると思います。

I believe two types of people can resist this punishment.

(1) これらの勉強という手段を軽々と扱うことのできる、いわゆる「頭の良い人間」。

(1) The so-called “smart people,” who can easily handle study as a mere tool.

彼らにとっては、どんな教科であれゲームのルールに過ぎず、そこに意味を求める必要はありません。

For them, any subject is nothing more than a game’s rules, and they do not need to find meaning in it.

(2) 『{英語、数学、国語、家庭科、others}なんて、何の役にも立たない』と割り切り、勉強しない覚悟をした人。

(2) Those who decide “these subjects are useless” and choose not to study, fully prepared for the consequences.

いわゆる「無敵の人」です。世間の規定する価値を拒み、不利益を承知で生きると決めた人です。

These are the so-called “invincible ones” who reject societal values and choose to live while accepting the disadvantages.

比して、上記(1)(2)に当てはまらない多くの人は、「今日掘った穴を明日には埋め戻す」という気持ちで、ティーンエイジャの期間を「懲役」と諦めて過ごすのでしょう。

By contrast, most people who do not fit (1) or (2) resign themselves to their teenage years as “punishment,” feeling like they are endlessly digging and refilling holes.

では、なぜ人類は「{英語、数学、国語、家庭科、others}」という、一見無意味な穴掘りを制度として続けているのでしょうか。

Then why has humanity institutionalized this seemingly meaningless hole-digging called “study”?

理由は単純です。社会は、子どもを「無意味な作業に耐えられる大人」に仕立て上げる必要があるからです。

The reason is simple: society needs to train children into adults who can endure meaningless tasks.

会社に入れば、会議資料を作っては上司に破棄され、作り直してはまた破棄される。

In the workplace, you create presentation materials only for your boss to discard, remake, and discard again.

書類の99%は誰も読まないし、会議の8割は誰の記憶にも残らない。

99% of documents are never read, and 80% of meetings leave no memory in anyone’s mind.

それでも席に座り続けなければならない。

Yet you must remain seated.

つまり、大人の社会の本質こそが「今日掘った穴を明日埋め戻す」ことなのです。

In other words, the essence of adult society is precisely “digging a hole today and filling it tomorrow.”

実は、この点については私、すでに述べたことがあります。

In fact, I have already written about this point.

このように考えていくと、

Thinking this way,

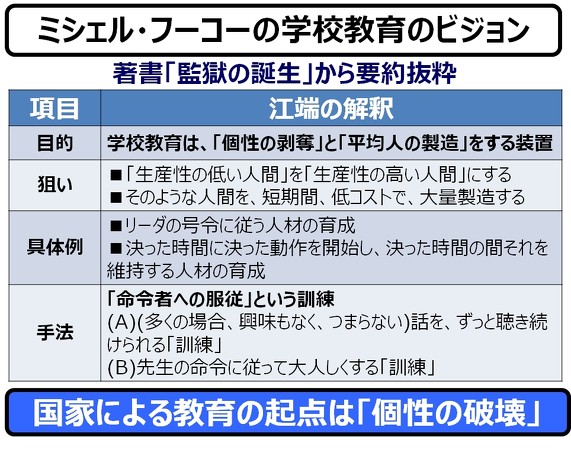

―― 学校教育は、子どもに知識を教えているように見せかけて、実際には「穴掘り訓練」をしている

School education appears to teach children knowledge, but in reality, it is “hole-digging training.”

という結論になります。

That is the conclusion.

これはかなり悲しい結論です。

This is quite a sad conclusion.

「穴掘り訓練」をやらされているのであれば、その「穴掘り」を自分のためにカスタマイズできないものか、と誰しも思うでしょう。

If one is forced into “hole-digging training,” anyone would wonder whether the digging could be customized for their own sake.

できれば、楽しくてやる気の出る方向に。

Ideally, toward something enjoyable and motivating.

そして、ここで一つ疑問が浮かびます。

And here arises a question.

学校教育の第一の目的は「個性の破壊」と「人間のスペックの画一化」であるとすれば、逆に「個性が破壊されず」かつ「画一的なスペック化が施されず」に育成された子どもは、将来どうなるのか。

If the primary purpose of school education is “the destruction of individuality” and “the standardization of human capability,” then conversely, what becomes of children whose individuality remains intact and whose capabilities are not standardized?

■楽観的見解

■ Optimistic view

個性を保持し、画一化されない教育を受けた子どもは、従来の教育制度では潰されてきた“異才”をそのまま発揮できる可能性があります。

Children who keep their individuality and are not standardized may unleash the “exceptional talents” that the traditional system would have crushed.

社会において「大量生産型の人材」がAIや機械に置き換えられていく時代、むしろ“没個性的な人間”こそ余剰となり、独自性を保った人間が生き残る。

In a society where “mass-produced human resources” are replaced by AI and machines, it is the “non-individualistic humans” who become surplus, while those who keep their uniqueness survive.

結果として、彼らは社会の変革者や次世代のリーダーとなり得るでしょう。

As a result, they could become the reformers of society and the next generation of leaders.

■悲観的見解

■ Pessimistic view

しかし一方で、社会の共通ルールに適応できない“異物”となる危険も大きい。

On the other hand, there is a substantial risk of becoming “misfits,” unable to adapt to society's standards.

社会は“平均的に働ける人材”を前提に設計されており、出勤時間を守れない、命令に従えない、協働できない人間は「扱いづらい」として排除されやすい。

Society is designed on the assumption of “average workers,” so those who cannot follow schedules, obey orders, or collaborate are easily excluded as “difficult to handle.”

学校教育が“個性を削る”ことで歯車に収めてきたのをやめれば、その子どもは歯車に組み込めず、結果的に孤立や不適応に追い込まれる。

Without school education, reducing individuality to fit into the gears, such children cannot be integrated into the system and end up isolated and maladapted.

つまり「個性破壊」機能が、実は社会の潤滑剤でもあったという皮肉に行き着きます。

In other words, the function of “destroying individuality” turns out, ironically, to have been society’s lubricant.

と、まあ、今回の検討はここまでとします。

Therefore, I will conclude this consideration here for now.

いずれにしても、「子どもの個性を大切に育てるべきだ」と叫ぶ大人は、案外「子どもを死地に送る準備をしている」ことに気づいていないのかもしれません。

In any case, adults who shout “we must nurture children’s individuality” may unknowingly be preparing them for a death trap.

私なら、『考えて、考えて、考え抜いたが、それでも正解が分からない』という大人の方が、まだ信じられる気がします。

As for me, I feel I can trust the adults who say, “I thought and thought and thought again, but I still don’t know the right answer.”