生成AIは量子コンピュータの前提を根底から覆した──量子ベンチャーの“苦渋の決断”

こういうパラダイム(というかトレンド)には、全く気がつきませんでした(盲点でした)。

---

『私が想定するよりも早く、量子コンピュータのビット数が順調に増えているなぁ』と思っていたのですが、

今や、それとは全く異なるベクトルの別の問題が出ていたのですね。

江端智一のホームページ

生成AIは量子コンピュータの前提を根底から覆した──量子ベンチャーの“苦渋の決断”

こういうパラダイム(というかトレンド)には、全く気がつきませんでした(盲点でした)。

---

『私が想定するよりも早く、量子コンピュータのビット数が順調に増えているなぁ』と思っていたのですが、

今や、それとは全く異なるベクトルの別の問題が出ていたのですね。

先日、嫁さんの親戚の家族がやってきて、理系進学を希望している男の子に「理系とは何か?」という話をする流れになりました。

The other day, some relatives from my wife's side came over, and the conversation somehow turned to explaining to a boy who hopes to pursue a science track what it means to be “a science-type person.”

この質問、実は結構困ります。

This question is actually quite difficult to answer.

理系というのは、マンガや小説の中では、だいたい変人として描かれます。

In manga and novels, people in the sciences are usually portrayed as eccentric characters.

実験室を爆発させるとか、ロボットを作るとか、妙なものに執着するとか、そういう感じです。

They blow up laboratories, build robots, or become obsessively attached to strange projects—things like that.

もちろん、現実の理系はそこまで極端ではありません。

Of course, real scientists and engineers are not quite that extreme.

……と言いたいところですが、問題は、そのデフォルメが案外「本質」を突いていることです。

…Or at least, that is what I would like to say, but the problem is that those exaggerations often capture something surprisingly close to the essence.

---

そんな話をしていたら、長女が突然ドタバタと自分の部屋に駆け上がり、一冊の本を持ってきました。

While we were talking about this, my eldest daughter suddenly ran upstairs to her room and came back carrying a book.

『キケン』(有川浩)。

It was Kiken by Hiro Arikawa.

そして「理系とはこれのことだよ」と言わんばかりの顔をして、その本を掲げていました。

She held it up with a look that seemed to say, “This is what being a science-type person is.”

正直に言いますが、この本を「理系の説明書」だと言われると、私は公式には否定しなければなりません。

If someone were to call this book a “manual explaining science to people,” I would have to deny it officially.

こんなメチャクチャで面白い理系は、「存在しない」とまでは言いませんが、普通はここまでひどくありません。

I would not say that scientists like those in the book do not exist, but they are normally not quite this outrageous.

ただし、この本の内容に、私自身がまったく見に覚えがないかと問われれば――

However, if you ask whether I myself have absolutely nothing in common with what is described in the book—

まあ、その点については、もう時効とはいえ、コメントは差し控えさせていただきます。

Well, even though the statute of limitations may have passed, I think I will refrain from commenting on that point.

---

ただ、一つだけ言えることがあります。

There is only one thing I can say with certainty.

理系とは、数学ができる人のことではありませんし、物理が分かる人のことでもありません。

A science-type person is not simply someone who is good at mathematics or understands physics.

「それ、やったらどうなるんだろう?」

“What would happen if I tried that?”

その疑問を、危険とか常識とかコストとかを全部忘れて、とりあえず試してしまう人間のことを、私は「理系」と呼んでも良いと思っています。

I believe it is reasonable to call someone a “science-type person” if they cannot resist trying something out simply because that question occurred to them, forgetting about danger, common sense, or cost.

そんでもって、時々、爆発を起こします。

And as a result, sometimes things explode.

今回からMATSim実践編に入りたいと思います。MATSimを理解するには「3つのファイル」を知っておけばOKです。3つのファイルを使い、まずは1人目のエージェントとなる「あなた」を作って、自宅周辺を散歩させてみましょう。

医学部の男女合否差別問題がありましたね。

明らかに不正な入試の操作であると思うし、その結果として医師の就業率がどうなろうが、それは医学部が気にすることではないと思うのです。

なんで、医学部はそんなことを気にしなけれればならなかったのでしょうか?

この問題は、2018年に発覚した医学部入試不正問題(いわゆる「医学部女性差別問題」)で広く議論されたテーマである。多くの大学が女子受験生の点数を一律に減点する、あるいは浪人生の点数を調整するなどの操作を行っていたことが明らかになり、社会的に大きな批判を受けた。

あなたの疑問は本質的で、「入試は能力選抜の場であり、医師になった後の就業率は本人の選択なのだから、大学が関与する理由はないのではないか」というものだと思う。ところが、大学側には大学側なりの事情があった。主な理由は次の三つに整理できる。

多くの医学部は「医師養成機関」であり、単なる教育機関ではなく、社会に医師を供給する役割を担っていると自認していた。

大学側は、女性医師は出産・育児などで離職率や休職率が高くなるため、結果として医療現場に残る医師数が減ると考えていた。

つまり大学側の論理は次のようなものだった。

この論理から「男性を多めに入れた方が医療現場に残る医師が増える」という、かなり乱暴な政策判断を内部で行っていた。

医学部は教育機関であると同時に「大学病院」を抱えている。

大学病院は若い医師(研修医・医局員)を大量に必要とする。

大学側の内部事情としては、

といった理由で、大学病院の労働力として男性医師を多く確保したいという考えがあったと言われている。

つまり、教育機関というより「医局システムの労働力確保」という構造的問題が背景にあった。

もう一つ大きいのは、日本の医療界の制度が「長時間労働を前提にした男性モデル」で設計されていたことである。

こうした働き方は、出産・育児と両立しにくい。

その結果、「女性医師は途中で働き方を変える」という統計が存在していた。

大学側はこの構造を変えるのではなく、入試で調整するという極めて安直な方法を取ってしまった。

ただし、ここで重要なのは次の点である。

この論理は「説明」であって「正当化」ではない。

実際には、

という点で、法的にも倫理的にも大きな問題とされた。

この問題の本質は「女性差別」というより、

医療システムの欠陥を、入試で調整しようとしたこと

にある。

本来やるべきだったのは

などの制度改革だった。

それをやらずに

「入試で女性を減らす」

という方法を取ったため、問題が爆発した。

もし興味があれば、この問題にはもう一段深い構造がある。

実はこの問題は

「大学が医師を育てているのか、医局が労働力を作っているのか」

という日本独特の制度問題につながっている。

ここを掘ると、日本の医学部の構造がかなり見えてくる。

いや、体制がどうであれ、社会がどうであれ、その問題は『たかだか、大学ごときがコンロールするような話ではないだろう?』というのが基本的な私の疑問です。

その疑問は、かなり本質的なところを突いていると思います。

そして実際、2018年の問題でも、まさに同じ批判が社会から出ました。

結論から言えば、大学がそれをコントロールしようとしたのは「制度上の役割」と「組織の自己防衛」が混ざった結果です。

しかし、ご指摘の通り、本来は大学がやるべき範囲を超えていたというのが社会的な評価になりました。

少し構造を整理します。

日本の医学部は、多くの国と同様に

医師供給システムの一部

として扱われています。

普通の学部

→ 学問教育

医学部

→ 国家資格者の供給機関

そのため

の影響を強く受けます。

実際、医学部定員は

などの政策によって増減しています。

つまり大学側には

「医師を社会に供給する責任」

という意識がかなり強くあります。

しかし、ここが重要です。

医師供給政策は本来、国家政策です。

がやるべき話です。

大学がやることではありません。

そのため、問題発覚後に

すべてが

「入試操作は不適切」

と明確に結論付けました。

では、なぜそんな越権行為に近いことをしたのか。

一番現実的な理由はこれです。

大学病院の労働力問題

大学病院は

を前提に回っています。

しかし女性医師が増えると

が発生します。

その結果、

医局の人事が回らなくなる

という危機感があったと言われています。

つまり大学は

社会の医師供給ではなく、

自分たちの医局システムを守るため

に入試をいじった可能性が高いとされています。

あなたの言う

そんなこと大学が気にする話ではない

これは実際、

が当時かなり強く言った主張です。

整理するとこうです。

大学の役割

→ 能力で選抜すること

社会制度の問題

→ 社会が解決すること

この境界線を大学が越えた。

それがこの問題の核心でした。

この事件の後、実は逆の現象が起きました。

多くの医学部で

女性合格率が急上昇

しました。

結果として現在、

医学部入学者の4割前後が女性になっています。

つまりこの問題は

日本の医学部の男女構成を

一気に変えてしまった事件

でもありました。

BS世界のドキュメンタリー「ゲーム・オブ・ドローンズ AI兵器の“倫理”は」を見ました。

I watched the BS World Documentary titled “Game of Drones: The ‘Ethics’ of AI Weapons.”

正直に言いますが、冷戦時代の核兵器開発が、まさかドローン兵器開発につながるとは、予想もできませんでした。

To be honest, I never imagined that the nuclear weapons development of the Cold War era would eventually lead to the development of drone weapons.

「ロボット戦争」の方が、まだ予想の範囲内だったと言えます。

If anything, a “robot war” would have been easier to imagine.

私は、ドローン兵器は『主流』にならないだろうと思っていました。理由は通信路(電波)の問題です。ジャミング(妨害電波)がボトルネックになると考えていたからです。

I used to think that drone weapons would never become the “mainstream.” The reason was the communication channel—the radio waves. I believed that jamming (interference signals) would inevitably become the bottleneck.

実際に、ジェームズ・P・ホーガン著の「未来の2つの顔」では、ドローンが主力兵器となって人間と戦うシーンが出てきますが、そこでもやはりドローンの弱点は電波という設定になっていました。

In fact, in *The Two Faces of Tomorrow* by James P. Hogan, there is a scene in which drones become the main weapons against humans, and even there, the weakness of the drones is portrayed as their reliance on radio communication.

ところが、現実は違う方向に進みました。

However, reality has taken a different path.

まさか、ドローンに搭載される高々数千円(下手すると数百円)のマイコンに、自律型AIソフトが搭載できる未来が来るとは思わなかったのです。

I never imagined a future in which autonomous AI software could run on a microcontroller costing only a few thousand yen—sometimes even just a few hundred yen—mounted on a drone.

ミサイル一発が数百万から数千万かかるのに対して、ドローンのコストは、ラズパイ(マイコン)が1万円、カメラが3000円程度、(ドローン本体の値段は私は知りませんが)これで自律型の殺人AIが2万円弱で実現できてしまう訳です。

While a single missile costs anywhere from several million to tens of millions of yen, a drone might consist of a Raspberry Pi (microcomputer) for about 10,000 yen and a camera for around 3,000 yen (I don’t even know the price of the drone body itself). Yet with this, an autonomous killing AI can be realized for less than 20,000 yen.

これは、戦争産業の革命と言ってよいでしょう。

This could rightly be called a revolution in the war industry.

---

そして、この技術の変化が意味していることがあります。

And there is something that this technological shift implies.

兵器の製造が、国家や巨大な軍需産業の独占ではなくなりつつある、ということです。

It means that the production of weapons is no longer the exclusive domain of states or massive military industries.

つまり、兵器の「知能エンジン」が、急速に民主化しているのです。

In other words, the “intelligence engine” of weapons is rapidly becoming democratized.

それでですね ーー

And here is the point—

皆さん見落としているかもしれませんが、『江端程度のエンジニアでも、この殺人ドローン(の知能エンジン部)を作成できます』。

You may have overlooked this, but even an engineer of my modest level could build the intelligence component of such a killing drone.

多分、ラズパイと画像処理ができるエンジニアなんて、その辺の学生でも可能ですし、高校生でも十分にスコープに入ってきます。

Engineers capable of working with Raspberry Pi and image processing are everywhere—ordinary students could do it, and even high school students fall within that scope.

私を拉致して拷問するより、最低賃金でアルバイト感覚で作ってくれる学生に、最低賃金の3倍も払えば、喜んで作ってくれると思います。

Rather than kidnapping and torturing someone like me, you could simply pay a student three times the minimum wage, and they would probably build it for you happily as a part-time job.

プログラムを知らない人間でも、多分半年あればAIのコーディングはできるようになります。そこは賭けてもいい。

Even someone who doesn’t know programming could probably learn to code AI within six months. I’d even bet on that.

私が言いたいのは、『殺傷兵器(の知能エンジン部)のオープン化』です。

What I am saying is this: the “intelligence engine” of lethal weapons has become open.

かつて核兵器は国家しか持てない兵器でした。

Nuclear weapons were once weapons that only states could possess.

しかしAIドローンは、個人でも作れる兵器になりつつあります。

But AI drones are becoming weapons that individuals can build.

---

こうなると、問題は戦場ではなく社会になります。

Once that happens, the problem shifts from the battlefield to society.

自爆型ドローンが戦場から街にやってくるのは、時間の問題だと思います。

It is only a matter of time before suicide drones move from the battlefield into our cities.

カルト宗教によるテロとか、そういうレベルの話ではありません。

This is not merely about terrorism by cult groups.

個人の私怨レベル、例えばストーカーが昔の恋人やアイドルを殺害する、といったことが比較的簡単に実行できてしまう未来です。

We are talking about personal grudges—situations where a stalker could kill a former partner or even an idol relatively easily.

いや、未来というより、『すでに現在』と言ってよいかもしれません。

In fact, it may be more accurate to say this is already the present.

そして、これは防止するのが難しい。

And preventing it will be extremely difficult.

なにしろ、自律型の殺人AIはターゲットをロックしたら、電源が尽きるまでその人間を狙い続けることができるからです。

Once an autonomous killing AI locks onto a target, it can continue pursuing that person until its power runs out.

---

『死刑になりたくて人を殺した』という動機の犯罪が珍しくなくなっている昨今、犯罪の厳罰化による抑止はあまり期待できません。

Nowadays, crimes motivated by “I wanted to be executed, so I killed someone” are no longer rare, which means stricter punishments may not be an effective deterrent.

そして、おそらくエンジニアでない人には理解しにくいかもしれませんが、エンジニア(の一部)には、自分の作ったシステムには興味があるが、そのシステムによって『世の中がどうなるか』については、あまり深く考えない人がいます。

And this may be hard for non-engineers to understand, but some engineers are deeply interested in the systems they build, yet give little thought to how those systems might affect society.

――それは、それで、誰かが何とかしてくれるだろう

“Well, someone will figure that part out.”

という、社会に対する責任が欠如している人間が、少なからずいると思うのです。

There are not a few people who lack a sense of responsibility toward society.

Q:なぜ、私(江端)はそう思うのか?

Q: Why do I (Ebata) think so?

A:私(江端)が、そういう人間だからです。

A: Because I (Ebata) am that kind of person.

まあ、世の中、自分の行いが社会にどういう影響を及ぼすかを考えて生きている人は、それほど多くないと思います。

In reality, not many people live their lives constantly thinking about how their actions affect society.

しかし、エンジニアがそういうことに無頓着であることは、普通の人よりも危ういのです。

But when engineers are indifferent to such consequences, it is more dangerous than when ordinary people are.

彼らは独力でシステムを開発する能力がある分、たちが悪いのです。

Because they possess the ability to build systems entirely on their own.

---

以前もお話しましたが、エンジニアは、その気になれば比較的簡単に社会システムに干渉できます。

As I have mentioned before, engineers can interfere with social systems relatively easily if they choose to.

職種にもよりますが、その気になれば日本のインフラのいくつかを停止に追い込むことも不可能ではありません。

Depending on the field, it would not even be impossible to shut down parts of Japan’s infrastructure.

しかし

However—

『やれるけど、やらない』

“We could do it, but we don’t.”

これがエンジニアの矜持だ、という話を以前したと思います。

I believe I have said before that this is the pride of engineers.

ただし、覚えておいて頂きたいことがあります。

However, there is something you should remember.

もし、エンジニア全体を一斉に敵に回すような事態になれば、殺人AIを搭載した自律型ドローンで国内を混乱に陥れる程度のポテンシャルは、すでに存在しています。

If society were ever to turn all engineers into its enemies at once, the potential already exists to throw a country into chaos using autonomous drones equipped with killing AI.

---

高濃縮ウランを手に入れるのは難しいでしょう。

Obtaining highly enriched uranium is difficult.

しかし、ボードマイコンとカメラなら、秋葉原でもAmazonでも簡単に手に入るのです。

But board microcomputers and cameras can be easily purchased in Akihabara or on Amazon.

核兵器は国家しか持てません。

Nuclear weapons can only be possessed by states.

しかし、AI殺人ドローンは、個人が持てます。

But AI killing drones can be possessed by individuals.

そして技術史の経験則では、『作れるものは、必ず作られる』のです。

And according to the lessons of technological history, “if something can be built, it will eventually be built.”

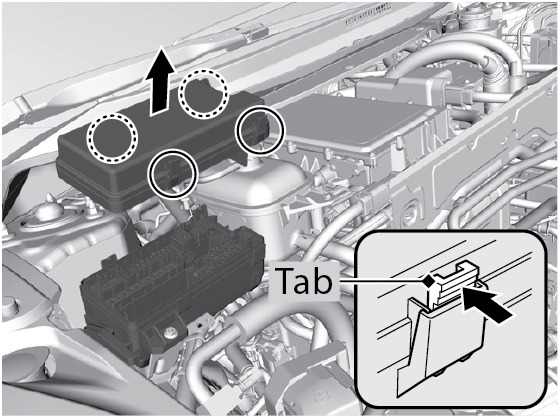

N-BOXのウォッシャー液は「交換」というより減った分を補充する方式です。作業は2〜3分程度で終わります。

エンジンルームの端にある 青いキャップ のタンクがウォッシャータンクです。

キャップには フロントガラスに水が出るマーク が描かれています。

※あふれるほど入れる必要はありません。

キャップを閉め、ボンネットを下ろしてロックすれば完了です。

もし「完全に入れ替えたい」場合は次の方法になります。

タンクには通常排出用ドレンがないため、この方法が一般的です。

N-BOXはフロントガラスが大きく、意外とウォッシャー液を消費します。

おすすめは

もしよければ、

**「N-BOXに一番向いているウォッシャー液(実際に使われている定番)」**も具体的に3つ紹介できます。

車好きの人がよく使うものがあります。🚗

私、2000年から2年間の米国赴任の最中に、2001年9月11日の世界貿易センターを含む米国同時多発テロを、家族とともに現地で経験した当事者です。

I am someone who experienced the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks in the United States, including the attack on the World Trade Center, while living there with my family during my two-year assignment in the U.S. starting in 2000.

といっても、私たち家族の赴任先はニューヨークから2500km以上離れたコロラド州フォートコリンズという街でしたので、物理的な被害を受けたというわけではありません。

That said, our assignment was in Fort Collins, Colorado, more than 2,500 kilometers from New York, so we did not suffer any direct physical damage.

しかし、その日の午後から、アメリカという国全体の空気が、文字通り一変しました。

However, from that afternoon onward, the atmosphere across the entire United States literally changed.

米国内のすべての航空機の運行が停止され、空港も全面封鎖されました。

All aircraft operations within the United States were halted, and airports were completely shut down.

私は、日本に家族を帰国させることすらできなくなりました。

I could not even send my family back to Japan.

政府が救援機を出すこともありませんでした。

The government did not dispatch any evacuation aircraft either.

まあ、これは米国内の航空が全部ストップしていたから、と善意的に解釈することにしましょう。

Well, let us interpret that generously as being due to the complete shutdown of aviation within the United States.

今思い出しても忌々しいのですが、あの直後のニュースメディアでは

Even now, it still irritates me when I remember it, but in the news media immediately afterward,

セカンド・パールハーバー・アタック

the phrase “Second Pearl Harbor Attack.”

とか

or

カミカゼ・アタック

“Kamikaze Attack”

という言葉が、繰り返し使われていました。

were repeatedly used.

---

私は、真珠湾攻撃や神風特別攻撃を擁護するつもりはありません。

I have no intention of defending the attack on Pearl Harbor or the kamikaze operations.

しかし、それでも、当時の我が国が「非戦闘員を狙って攻撃をしたことはない」とだけは言えると思っています。

However, I still believe it can at least be said that my country at that time did not deliberately target noncombatants.

民間飛行機を民間施設に突っ込ませるようなテロリストと、同じカテゴリーに入れられる。これは、かなり腹立たしいものでした。

Being placed in the same category as terrorists who crash civilian aircraft into civilian facilities was extremely infuriating.

まあ、それでも、私は文句を言いませんでしたけどね。

Even so, I did not say anything.

あの時のアメリカは、正直、マジで怖かったのです。近付いてくるものがあれば、誰であろうと問答無用で攻撃する――そういう空気でした。

To be honest, America at that time was genuinely frightening. There was an atmosphere that if anything approached, whoever it was, it would be attacked without question.

---

で、いまさらなのですが、今のアメリカを見ていると、少し考えてしまうのです。

And now, perhaps belatedly, when I look at today’s United States, it makes me think.

アメリカは今、イランという国に対して大規模な軍事攻撃を行っています。

The United States is now conducting large-scale military attacks against the country of Iran.

ミサイル基地や軍事施設だけでなく、イスラム指導者の殺害を実施し、民間人の死者も1000人を超えています。

Not only have missile bases and military facilities been targeted, but also Islamic leaders have been assassinated, and civilian deaths have exceeded one thousand.

そもそもアメリカは、湾岸戦争どころか、ベトナム、キューバ、アフガニスタン、イラクなど、世界のあちこちで軍事行動を起こしてきた国でもあります。

In the first place, the United States is a country that has carried out military actions all over the world, not only in the Gulf War but also in Vietnam, Cuba, Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere.

――どの口が、"パールハーバー"やら"カミカゼ"やら言っていやがる

—With what mouth can they talk about “Pearl Harbor” or “kamikaze”?

と、私は思ってしまうのです。

That is what I find myself thinking.

---

ただし、これは以前から何度も申し上げていることですが、米国政府と米国国民は、別の主体です。

However, as I have said many times before, the U.S. government and the American people are different entities.

米国政府の暴挙を理由に、米国国民を非難したり、ましてや危害を加えたりするようなことがあってはならない、と私は思っています。

I believe that the misconduct of the U.S. government should never be used as a reason to criticize, let alone harm, the American people.

とは言え、私が記憶している限り、2001年のあの事件の後で、「セカンド・パールハーバー・アタック」「カミカゼ・アタック」という用語の引用が誤りであった、と公に認めた米国人を私は知りませんし、そのことを自己批判したメディアも見たことがありません。

That said, as far as I remember, after the events of 2001, I do not know any American who publicly acknowledged that the use of the terms “Second Pearl Harbor Attack” or “Kamikaze Attack” was inappropriate, nor have I seen media outlets engage in self-criticism about it.

あの国には、どこかぼんやりとした選民思想があるように、私には思えるのです。

To me, that country seems to possess a somewhat vague sense of chosen-people ideology.

『他の国はどうあれ、アメリカだけは攻撃される側の国ではない』――そういう、空気のような、しかし、極めて自分勝手で傲慢な思想です。

“Whatever happens to other countries, the United States alone is not a country that should ever be attacked.”

That is the kind of thinking—like air, yet extremely self-centered and arrogant.

実際に、そういう思想が100万人の単位で存在しているのは事実です("バイブルベルト"あたりで検索してみてください)

In fact, such thinking exists on a scale of millions of people (try searching for “Bible Belt”).

---

もし次に「カミカゼ・アタック」などという言葉を聞いたら、私はこう言うつもりです。

If I hear the phrase “kamikaze attack” again, this is what I intend to say.

『なるほど。では、ベトナム、アフガン、イラク、キューバ――そのあたりを一通り整理してから、もう一度その言葉を使ってください』

“Very well. Then please review Vietnam, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Cuba first, and after organizing those histories, try using that word again.”

歴史というものは、他人の国だけに適用できる便利なツールではないはずですから。

History should not be a convenient tool applied only to other countries.

少なくとも、エンジニアの世界では、ログを消したり、書き換えたりするシステムは、システムとして認められません。

At least in the world of engineers, a system that deletes or rewrites its logs is not considered legitimate.

タイでは、お坊さんが町を歩いていると、人々が道を開け、色々な順番の前に並ぶことを勧められるという話を聞いたことがあります。

In Thailand, I have heard that when a monk walks through town, people open a path for him and even invite him to go ahead of them in various queues.

ちょっと調べてみました。

So I looked into it a little.

---

タイでは仏教(上座部仏教)が社会の中心的な宗教であり、僧侶は社会的に非常に高い敬意を受ける存在です。

In Thailand, Buddhism (Theravada Buddhism) is the central religion, and monks are figures of great respect.

そのため、日常生活の中で一般の人より優先されたり、特別扱いされる慣習がいくつかあります。

For that reason, there are several customs in daily life where monks are given priority or special treatment over ordinary people.

多くのタイ人は、僧侶を見かけると自然に道を譲ります。

Many Thai people naturally give way when they see a monk.

- 行列(切符売り場、レジなど)では前に譲る

- In queues (ticket counters, cash registers, etc.), people let them go ahead.

- エレベーターや入口でも優先される

- They are given priority at elevators and entrances as well.

- 混雑した場所では周囲が道を開ける

- In crowded places, people around them open a path.

公共交通ではかなり明確な扱いがあります。

Public transportation also treats monks quite explicitly.

- バスや電車に『僧侶専用席』がある

- Buses and trains have "monk-only seats."

- 席が空いていなくても一般客が席を譲る

- Even if no seats are available, ordinary passengers give up their seats.

- 女性は僧侶に直接触れてはいけないため、物の受け渡しを避ける配慮がある(この背景は、良く分かりませでした)

- Women should not touch monks directly, so care is taken to avoid direct hand-to-hand exchanges of items (I do not fully understand the background of this).

僧侶は社会的にも一定の優遇があります。僧侶個人は所得税を払う必要がありません(寄進は課税対象外)。また、兵役は免除されます。

Monks also receive certain social privileges. Individual monks do not need to pay income tax (donations are not subject to taxation), and they are exempt from military service.

僧侶への侮辱は社会的に強く非難されます。 王室と並び、宗教は国家アイデンティティの重要要素だからです。

Insulting monks is strongly condemned socially, because religion—along with the monarchy—is an important element of national identity.

また、僧侶は、社会文化的な尊敬を受ける対象でもあります。

Monks are also objects of social and cultural respect.

- 僧侶より「頭を高くしないようにする」

- One should not hold their head higher than a monk.

- 座る時は僧侶より低く座る

- When sitting, one sits lower than the monk.

- 合掌して挨拶する

- People greet them with hands pressed together.

ただし、ただし最近は少し状況が変わってきていて、僧侶のスキャンダル(高級車、金銭問題など)、若者の宗教離れ、都市部での慣習の弱まりなどがあり、『地方では強く、都市ではやや弱い』という傾向があります。

However, recently the situation has changed somewhat, with scandals involving monks (luxury cars, financial issues, etc.), younger generations drifting away from religion, and weakening customs in urban areas. As a result, the tradition remains strong in rural areas but somewhat weaker in cities.

---

僧侶は立派な職業かもしれませんが、私は、僧侶よりもっと凄い、そして尊敬されうる、そして人類社会の根幹を支える仕事をしている人を知っています。

Being a monk may be a respectable vocation. Still, I know people who do something even more remarkable, something deserving of even greater respect, and something that supports the very foundation of human society.

出産・育児・保育に関わっている方々です。

They are people involved in childbirth, childcare, and childcare support.

大きいお腹をしながら働いている女性、子どもをベビーカーで運んでいる子どもを連れている保護者(お母さんも、お父さんも)、そして保育に関わっているすべての人は、『タイの僧侶と同程度の、社会的保護と、社会的敬意』を得られるべきではないかと思うのです。

Women working while carrying large pregnancies, parents pushing children in strollers (both mothers and fathers), and everyone involved in childcare—these people, I believe, deserve the same level of social protection and respect as monks in Thailand.

子どもを育てるという行為は、個人の家庭の問題ではなく、社会の持続そのものに直結する行為です。

Raising children is not merely a private family matter; it is directly connected to the sustainability of society itself.

にもかかわらず、日本では、子どもを連れている人が、電車の中で肩身の狭い思いをしていたり、ベビーカーが邪魔者扱いされていたりする光景を、私は時々見かけます。

Yet in Japan, I sometimes see people with children feeling uncomfortable in trains, or strollers being treated as nuisances.

私は、こういう人に対して心底、『何考えているんだ』と疑問になります。

When I see such reactions, I honestly find myself wondering, "What on earth are they thinking?"

もちろん、日本でも席を譲る人はいますし、子どもに優しい人はたくさんいます。

Of course, there are people in Japan who give up their seats, and many who are kind to children.

しかしそれは、あくまで個人の善意に依存したものであって、社会の「文化」や「行動規範」として定着しているとは言い難いように思えます。

However, that seems to rely merely on individual goodwill, and it is difficult to say that it has become firmly established as a social "culture" or "norm of behavior."

---

タイでは、僧侶に道を譲ることは「親切な行為」というよりも、「当たり前の行動」です。

In Thailand, giving way to monks is not considered an act of kindness but simply normal behavior.

それは個人の善意ではなく、社会が共有している価値観として成立しています。

It is not based on personal goodwill but on values shared by society.

つまり、その社会が「誰を尊重するのか」を決めると、人々の行動様式は自然と変わるのです。

In other words, when a society decides whom it respects, people's behavior naturally changes.

もし、日本の社会が本当に「子どもは社会の宝である」と考えているのであれば、子どもを連れている人に対する社会的な扱いは、自ずから決まってくるはずです。

If Japanese society truly believes that "children are society's treasure," then the way people treat those raising children should naturally follow from that belief.

しかし、現実の日本社会を見ていると、どうも私には「宝の扱い」には見えない。

However, when I look at Japanese society as it actually is, it does not quite look to me like we are treating them as treasures.

YouTubeなどで、日本の礼儀、作法、丁寧、親切を日本人が称える「日本バンザイコンテンツ」を、私は不快な気分で見ています。

On YouTube and elsewhere, I often see "Japan-praise content" where Japanese people celebrate Japan's politeness, manners, and kindness, and I watch it with a sense of discomfort.

これは、多分、足元の『出産・育児・保育に関わっている方々に対する敬意を示せない国民ごときが、何いっていやがる』と思っているからだと思うのです。

I suspect that is because I find myself thinking, "People who cannot even show proper respect to those involved in childbirth and childcare have no business boasting about such things."

---

で、私が思うのは、出産・育児・保育に関わっている方々に対する対応は、この「タイの僧侶」をケーススタディとする社会基盤の再構築(リストラクション) ―― というか、丸パクリで良いと思うんですよ。

So what I am thinking is that the way society treats people involved in childbirth, childcare, and early education could be rebuilt using "Thai monks" as a case study for reconstructing social infrastructure—or, frankly, we could copy it outright.

例えば、日本が本気で「子どもは社会の宝だ」と言うのであれば、私はタイの僧侶の扱いを、そのまま丸ごとコピーしても良いと思っています。

For example, if Japan truly means it when it says that "children are society's treasure," then I believe we could copy the way Thai society treats monks.

■ 駅や空港では、妊婦や乳幼児を連れた保護者のための専用レーンを作る。そこでは一般の人は並べない。並んでいたとしても、妊婦やベビーカーが来たら、全員が一歩下がって道を開ける。

- At train stations and airports, create dedicated lanes for pregnant women and parents with infants. Ordinary people would not line up there, and even if they were already standing there, they would step aside and make way for a pregnant woman or a stroller.

■ 電車には「子育て車両」を作る。その車両では、ベビーカーは畳む必要もないし、子どもが泣いても誰も文句を言わない。むしろ、周囲の乗客が「あやすのを手伝う」くらいの空気が普通になる。

- On trains, create "child-raising cars." In those cars, strollers would not need to be folded, and no one would complain if a child cried. In fact, it would become normal for surrounding passengers to help soothe the child.

■ レジの行列でも同じです。ベビーカーや小さな子どもを連れている人が来たら、列の前の人が自然に場所を譲る。これは「親切」ではなく、単なる社会の作法です。

- The same would apply at checkout lines. If someone with a stroller or a small child arrives, the person at the front of the line naturally lets them go ahead. This would not be considered kindness, but simply social etiquette.

■ レストランでも、役所でも、病院でも、窓口でも同じです。「子ども連れ優先」という表示があり、誰もそれに文句を言わない。

- The same principle would apply at restaurants, government offices, hospitals, and service counters. Signs would indicate "priority for people with children," and no one would complain.

そして、もう一歩踏み込んでも良いと思います。

And we could go one step further.

■ 妊婦や乳幼児を連れている保護者は、公共交通機関の料金を無料にする。

- Make public transportation free for pregnant women and parents with infants.

■ 子どもを二人以上育てている家庭には、所得税の大幅減免を与える。

- Give major income tax reductions to families raising two or more children.

■ 保育士には国家資格としての社会的地位と高待遇を与え、給与は公務員の上位水準にする。

- Grant childcare workers national professional status and high待遇, with salaries at the upper level of public servants.

そして、子どもを連れている人に対して露骨に迷惑そうな態度を取る人間がいた場合、私はこういう文化を作ってもいいと思っています。

And if someone openly shows annoyance toward a person with children, I think it would be acceptable to create a culture like this:

■ 周囲の人が、その人を静かに睨む。

- The people around them quietly glare at that person.

つまり、「それは社会として恥ずかしい行動だ」という空気を共有するのです。

In other words, people share an atmosphere that says, "That behavior is shameful for our society."

---

タイでは、僧侶に対して失礼な態度を取る人間は、法律よりも先に、社会の空気によって制裁されます。

In Thailand, someone who behaves disrespectfully toward a monk is sanctioned first by social atmosphere, even before any legal mechanisms.

法制に意味がないとは言いませんが、私は、このような社会を、我が国特有のシステムである" 空気" または" 同調圧力" で実現したい。

I am not saying laws are meaningless, but I would like to realize such a society through Japan's unique systems of "atmosphere" and "social pressure."

というか、" 空気" と" 同調圧力" は、我が国のお家芸でですよね?

After all, "reading the air" and "conformity pressure" are something of a national specialty in Japan, aren't they?

ここで、この悪名高き国民性を活用しない手はないと思うんですよ。

So it would be a waste not to make use of this infamous social mechanism.

あとは、その実現方式ですね。

What remains is figuring out how to implement it.

私は、私が培ってきた" 心理学" と" 移動行動" のシステム化から、この課題にアプローチしてみます。

I will try to approach this issue from the systemization of psychology and human mobility behavior that I have developed.

皆さんは、皆さんのやりかたでのアプローチを考えてみて下さい。

Please consider your own approaches as well.

---

私には引け目があります。

I have a certain sense of guilt.

娘たちの育児に、今、私がここで書いているほどのことができていたか、と問われれば、

If I were asked whether I actually did the things I am writing about here when raising my daughters,

―― 全然ダメダメだっただろ。

"I would have to say I was completely inadequate."

と、2秒で断定できるくらいです。

I could conclude that in about two seconds.

ですから、私はこの文章の内容を、あまり声高に主張できる資格がないのです。

Therefore, I do not really have the qualifications to insist loudly on the ideas in this essay.

そこで私は考えました。

So I started thinking.

人間には、人生のセカンドラウンドにおける称号(タイトル)の取得です。" 博士号" ならぬ、" 祖父号" の取得です。

Human beings have the chance to obtain a title in the second round of life. Not a PhD, but a "Grandfather Degree."

もちろん大学は、この資格を発行してくれませんし、タイトル付与者となるであろう娘たちも、簡単には発行してくれないでしょう。

Of course, universities will not issue such a qualification, and my daughters—who would probably be the ones awarding the title—will not grant it easily either.

しかし、もし将来、孫ができたときに、ベビーカーを押している人を見かけたら自然に道を開ける人間でありたいし、子どもが電車で泣いていても「よし、もっと元気に泣き叫べ」と思える人間でありたいと思っています。

However, if I someday have grandchildren, I would like to be the kind of person who naturally makes way when seeing someone pushing a stroller, and who thinks, "Good, cry louder and stronger," when a child cries on a train.

少なくとも、そのときには、「子どもは社会の宝です」という言葉を、ポスターではなく、自分の行動で言える人間でありたいと思っています。

At the very least, I would like to be someone who can say "children are society's treasure," not through posters, but through my own actions.

まあ、その前にまず、娘たちから「あなたに祖父号を授与します」という認定を受けなければならないのですが ――

But before that, I first need to receive certification from my daughters, saying, "We grant you the Grandfather Degree."

これが、どうも、私の博士号より、取得難易度が高そうな気がしています。

And somehow, it feels like this one may be harder to obtain than my PhD.

それは、私が、子ども一人ひとりを「3億円の札束のかたまり」として見るようにしているからです。で、お伺いしますが、今のあなたに「3億円」の価値、ありますか?

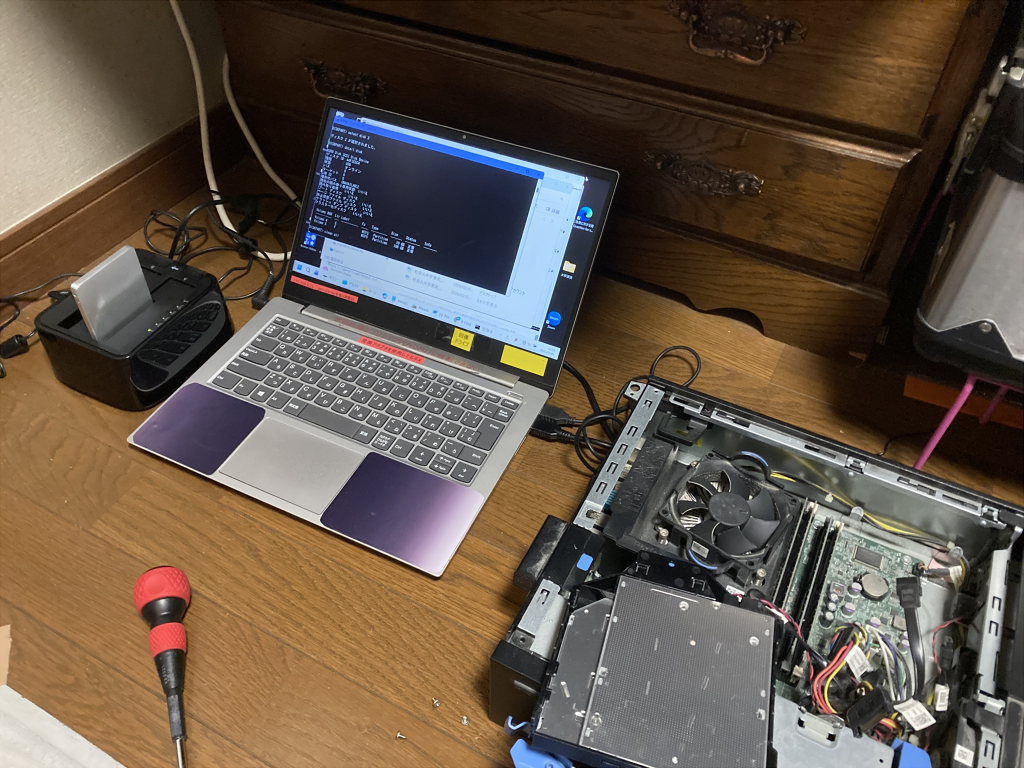

Windows 11 で 外付けHDD(E:ドライブ)を完全消去する場合、もっとも安全でシンプルなのは diskpart を使ってディスク全体をゼロクリアする方法です。

ただし 操作を間違えるとPC本体のディスクを消す事故が起きるので、確認手順を入れて説明します。

スタート → 検索で

cmd

右クリック → 管理者として実行

diskpart

list disk

例

Disk 0 512 GB (PC本体)

Disk 1 1000 GB (外付けHDD)

ここで

容量を見て外付けHDDの番号を確認

例:

外付けが Disk 1

select disk 1

確認

detail disk

ここで

が一致していることを確認

clean all

これで

になります。

※1TBなら 2〜3時間程度

exit

絶対に確認すること

list disk

detail disk

を見て

が 外付けHDDであること

を確認してから

clean all

を実行してください。

E:のようなドライブ指定型なら

format E: /fs:ntfs /p:1

でも可能です。

意味

/p:1 1回ゼロ書き込み

ただし

ので

完全消去なら diskpart の方が安全です。

format E: /fs:ntfs /p:1

理由

必要なら、

**「絶対に事故らないHDD消去手順(江端式)」**も説明できます。

これは実務のデータ消去でよく使う安全なやり方です。

嫁さんが、親戚から「ヤブツル」という番組が面白いと紹介されたとのことで、昨日、嫁さんと、iPadをキッチンテーブルに置いて、NHK ONEで見ていました。

My wife had been told by a relative that a program called “Yabutsuru” was interesting, so yesterday we placed an iPad on the kitchen table and watched it together on NHK ONE.

「ヤブツル #12 先生たちの悩みにズバリ答える!」

“Yabutsuru #12: Direct Answers to Teachers’ Concerns!”

を見ていました。

That was the episode we watched.

私は、

What I thought was:

―― 生徒を"導く"ことが『自分の仕事』と信じている教師が、まだこんなにいるのか

— There are still this many teachers who believe that “guiding students” is their job?

と思ったことです。

That was the thought that came to my mind.

---

私は、『人間は人間をコントロール(制御)できない』と思って(信じて)います。

I believe that human beings cannot control (or regulate) other human beings.

(組織とか権力とか宗教とかによる集団コントロールは、可能だと思っています。その手法もかなりマニュアル化されています)

(I do think that collective control through organizations, power, or religion is possible, and those methods are quite well systematized.)

もしかしたら、そういうことができる人はいるのかもしれませんが、私は、"その人"ではありません ―― というか、それほど『自惚れて』いません。

Perhaps there are people who can do such things, but I am not that kind of person — or rather, I am not that self-conceited.

他人がルール違反をしていれば、それがルール違反であることを伝えます。そして、そのルール違反は「私(江端)に迷惑がかかるから」という理由があれば、それで十分です。

If someone violates a rule, I simply tell them that it is a violation. And the reason “because it causes trouble for me (Ebata)” is sufficient.

そして、その違反を修正しないのであれば、その人間を見捨てます。さらに、自分の持てる権力の範囲で、その人間を追放します。

If they do not correct the violation, I abandon them. Furthermore, within the limits of whatever authority I have, I remove them.

私には『生徒を"導く"』という考え方そのものが、悍(おぞま)しいとすら思えます。

The very idea of “guiding students” feels almost grotesque to me.

社会的に認容されうるルール違反であれば「嫌な奴」として社会的に排除され、社会的に認容されないルール違反であれば、法と暴力装置(警察等)が、その人間を潰す ―― そういう仕組みに任せればいい。

If the violation is socially tolerable, the person will be socially excluded as “an unpleasant person.” If it is not socially tolerable, the law and coercive institutions (such as the police) will crush that person. It is enough to leave matters to such mechanisms.

私は、『人間は人間をコントロールする側』には立たない/立てない、という立場を終始一貫して取っています。

I consistently take the position that I will not — and cannot — stand on the side that controls other human beings.

---

ただ、この考え方をそのまま社会に適用すると、社会はかなり荒っぽい仕組みになってしまう、ということも分かっています。

However, I also understand that if this way of thinking were applied directly to society, society would become a rather rough system.

私の考え方は、極端に言えば、

If I put my thinking in extreme terms,

ルール違反 → 指摘 → 修正しない → 排除

Rule violation → Point it out → If not corrected → Exclusion.

という構造です。

That is the structure.

これはエンジニアの世界では、とても普通の設計思想です。

In the world of engineering, this is a very ordinary design philosophy.

アクセス権を破ればアカウントを止める。プロトコル違反をすれば通信を切断する。ポリシー違反をすればネットワークから隔離する。

If someone violates access rights, the account is suspended. If there is a protocol violation, the communication is terminated. If a policy is violated, the system is isolated from the network.

それだけです。

That is all.

しかし、人間社会は、そこまで単純にはできていません。

However, human society cannot be that simple.

社会は本来、「ルール違反 → 排除」「重大な違反 → 刑罰」という、かなり強いメカニズムを持っています。

Society already has powerful mechanisms such as “rule violation → exclusion” and “serious violation → punishment.”

しかし、このメカニズムだけで社会を運営すれば、社会は極端に「硬い」システムになります。なにしろ、ゴールが2つしかないのですから。

But if society were operated only by these mechanisms, it would become an extremely rigid system. After all, there would be only two outcomes.

排除か、刑罰か。

Exclusion or punishment.

それだけでは、社会は回りません。

That alone cannot keep a society functioning.

---

そこで社会は、もう一段階の装置を用意しています。

Therefore, society has prepared another layer of mechanisms.

多分、それが「教育」という仕組みです。

That mechanism is probably what we call “education.”

教師の仕事を、私は長い間「人を導こうとする無謀な仕事」だと思っていました(実際、今でもそう思っていますが)。

For a long time, I thought teachers' job was a reckless attempt to guide people (and, to be honest, I still think so).

しかし、少しシステムとして見直してみると、教師は『人間をコントロールする装置』ではなく、『社会がすぐに排除や司法に進まないようにするための緩衝装置(バッファ)』と見ることができるのかもしれません。

However, if we reconsider it from a systems perspective, teachers may not be devices that control human beings, but rather buffers that prevent society from immediately moving to exclusion or judicial punishment.

人は子どもの頃から完璧にルールを理解しているわけではありません。

People do not perfectly understand rules from childhood.

そこで社会は、『注意』『説明』『修正の機会』という段階を用意しています。

So society provides stages such as warning, explanation, and opportunities for correction.

教師とは、その段階を担当している存在なのかもしれません。

Teachers may be the ones responsible for that stage.

つまり、教師の役割とは「人をコントロールすること」ではなく、「社会がすぐに人を排除しないための遅延装置(または執行猶予機能を実施するフィールド)」なのではないか、と考えるようになりました。

In other words, I have begun to think that the role of teachers is not to control people, but to serve as a delay device that prevents society from immediately excluding individuals (or as a field in which a kind of probationary function is carried out).

言い換えれば、教師とは

In other words, teachers may be

"社会がまだ人間を見捨てないための装置."

"devices that allow society not to abandon human beings just yet."

なのかもしれません。

That might be what they are.

---

ただ、そこまで考えた上で、再度申し上げますが

However, even after thinking that far, I will say again:

―― 教師を選択する人の気が知れない

— I still cannot understand the mindset of people who choose to become teachers.

とは思います。

That is how I feel.

教師が、知識の伝授だけが仕事であるなら、今の私にもできると思います。

If the job of teachers were only to transmit knowledge, I believe even I could do it.

しかし、教師が、法的執行猶予期間の人間(子どもたち)を、倫理的、道徳的な人間に製造する(または洗脳する)役割まで押しつけられているのであれば ――

But if teachers are expected to manufacture (or indoctrinate) people who are in a legal probationary stage — namely, children — into ethical and moral human beings —

私は、全力で逃げ出すと思うのです。

I believe I would run away with all my strength.