――こんだけ高い税金を払っているんだ。私の死体処理の面倒くらい見ろ

以前、「孤独死」というのは、結構インパクトのある用語でした。

In the past, the term “lonely death” carried considerable impact.

だから「地域との繋がりを大切に」はともかく、「結婚しろ」「子どもを育てろ」という、物騒な脅迫に使われたものです。

So, aside from “cherish ties with the community,” it was often used as a menacing threat: “get married,” “raise children.”

ところが近年、「孤独死」というのは、もはや社会現象の一形態として一般化されつつあり、脅迫用語としては、あまり効果がなくなってきています。

In recent years, however, “lonely death” has become normalized as one form of social phenomenon, and as a threat, it has largely lost its effectiveness.

色々な人に話を聞いていますが、現在、目下の課題は「孤独死」ではなく、その前の「苦痛」と、その後の「遺体処理」――ぶっちゃけ「遺体の腐敗」に、スコープが移っているようです。

From conversations with various people, it seems that the current pressing issues are no longer “lonely death” itself, but the “suffering” before it and the “handling of the body” afterward—in plain terms, the decomposition of the corpse.

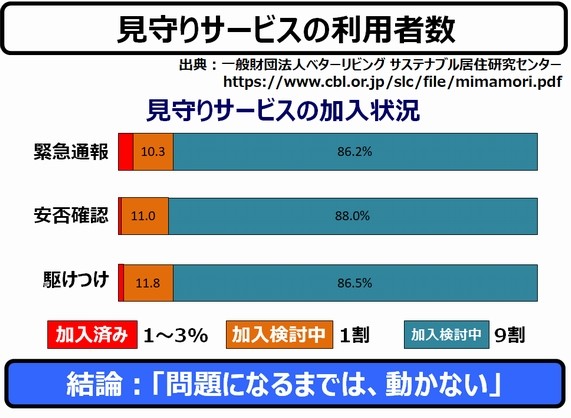

私、以前、「見守りサービス」が意味をなさない、という事実をロジカルに提示したことがあります。ところが、「見守りサービス」には、裏側の――といいつつ、実質的な機能があるのです。

I once logically demonstrated that “monitoring services” are largely ineffective. However, such services do have a hidden—though very real—function.

(↑Jump to the column)

「第三者による遺体発見」です。

That function is “discovery of the body by a third party.”

プライバシーの問題から、映像監視には課題がありますが、センサを使った動態監視は、比較的しきい値が低い。

Due to privacy concerns, video surveillance is problematic, but motion-based monitoring using sensors faces a much lower threshold of acceptance.

つまり、「24時間以上、動態をチェックできない → 死亡している確率が高い → 死体を本格腐敗の前に回収できる」という意義です。

In other words: “No detectable activity for over 24 hours → high probability of death → the body can be recovered before serious decomposition.”

これは、技術的には比較的簡単です。

Technically speaking, this is relatively simple.

動態センサの設置でもいいですし、電力消費量のチェックでも可能です。もっとも簡単なのは、スマホの利用状況を見ることでもできます。

It can be done through motion sensors or by checking electricity usage. The simplest method may even be monitoring smartphone usage.

これは、行政サービスとして組み込んでも、十分にペイしますし、賃貸アパートやマンションなら、契約条件として入れても、大きな問題にはならないでしょう。

This would pay off even as a public administrative service, and in rental apartments or condominiums, it could be included in contract terms without causing significant issues.

(江端家の場合は、玄関に設置したカメラが、移動時の映像を記録しています。私がDIYで作ったものです)

(In the Ebata household, a camera installed at the entrance records movement. I built it myself as a DIY project.)

---

私、大学で社会関係資本(ソーシャルキャピタル:SC)の勉強と合わせて、主観的幸福度(サブジェクティブ・ウェルビーイング:SWB)についても学んできました。

At university, alongside studying social capital (SC), I also studied subjective well-being (SWB).

で、このSCとSWBは、時として相反することがあるのですよね。

And these two—SC and SWB—can sometimes be in conflict.

「人との繋がり」が「苦痛」になるケースは、非常に多いですし、それが社会の現実だと思うのです。これを無理矢理、変えるのは、どうかと思うのです。

There are many cases where “connections with others” become a source of pain, and I believe this reflects social reality. Forcing this to change seems questionable.

一方で「誰にも迷惑をかけずに死にたい」という願望は、かなり昔から、日本人の標準装備です。これは、立派なSWBです。

The desire “to die without causing trouble to anyone” has long been part of the Japanese default mindset. This, too, is a legitimate form of SWB.

ただ、以前は、それを口にすると、「冷たい人」「人でなし」扱いされていただけの話で、欲望そのものが消えていたわけではありません。

Previously, expressing this desire merely led to being labeled “cold-hearted” or “inhumane”; the desire itself never disappeared.

---

つまるところ、「孤独死はダメ」という道徳論が、「腐敗は困る」という実務論に置き換わっただけです。

At present, the moral argument “lonely death is wrong” has been replaced by the practical argument “decomposition is a problem.”

そして、実務論に落ちた瞬間、解決策は一気に具体化します。

The moment the issue becomes practical, solutions rapidly take concrete form.

動かなくなる。電気を使わなくなる。スマホを触らなくなる――以上、三点セットでアラートを出せば十分です。

People stop moving. Electricity usage stops. Smartphones go untouched—those three indicators are enough to trigger an alert.

ここに「家族愛」も「地域コミュニティ」も登場せず、あるのは、センサと閾値と、担当者の業務フローだけです。

There is no mention here of “family love” or “community”; only sensors, thresholds, and operational workflows for staff.

この割り切りの良さ、私は嫌いではありません。

I don’t dislike this kind of clear-cut pragmatism.

---

むしろ、

Rather,

「結婚しろ」「子どもを作れ」「近所付き合いをしろ」という、人生フルコース前提の設計より、

Compared to a design that assumes a full-course life—“get married,” “have children,” “socialize with neighbors,”

「一人で生きて、一人で死ぬ前提で、社会が後処理する」という設計の方が、よほど多様性に配慮しています。

a design that assumes “living alone and dying alone, with society handling the aftermath” is far more considerate of diversity.

人間関係を強制しない社会。死に方だけは、きちんと管理する社会。冷たいようで、実はかなり優しい。そして何より、この仕組みは前向きです。

A society that does not force human relationships, yet appropriately manages death. It may seem cold, but it is actually quite kind—and above all, forward-looking.

なぜなら、「どう生きるか」を社会が指示しなくなり、「どう死ぬか」だけを、淡々と整備することになるからです。

Because society stops instructing people on how to live, and instead quietly prepares only for how death is handled.

生き方は自由。納税と労働の対価として、死後処理は国家の義務――という割り切り、私は、なかなか悪くないと思うのです。

Life choices are free. In return for taxes and labor, post-mortem handling becomes a duty of the state—this trade-off strikes me as not bad at all.

---

ただ、「私の死んだ後に、世界がどうなろうが知ったことか」というのも、割り切りの一つではあります。

That said, “I don’t care what happens to the world after I die” is also a form of detachment.

私は、これを否定するロジックを持ち得ません。

I have no logic with which to refute that stance.

まあ、だからこれは、「腐敗した死体を処理するコストを、誰に押しつけるか」というコスト問題に転換すれば良い。

So perhaps this is ultimately a question of who bears the cost of handling decomposed bodies.

孤独死する人は、大抵、縁者も少ないし、縁者がいたとしても、そのコストを支払うとは思えません。

Those who die alone usually have few relatives, and even if they do, it is unlikely they would pay those costs.

そう考えていくと、行政が動くのが、行政にとって一番安い、というキャッシュフローが成立すると思います。

Seen this way, a cash-flow logic emerges in which government intervention is the cheapest option for the government itself.

私は、

As for me,

――こんだけ高い税金を払っているんだ。私の死体処理の面倒くらい見ろ

“I pay this much in taxes. The least you can do is take care of my corpse.”

と言っても、良いと思うんですよね。

I think it’s perfectly reasonable to say that.