東京(関東エリア)は、昨年、大きな台風の被害もなく、洪水なども発生せず、そして、自衛隊が出動するという「住民の生存を左右しかねない」豪雪もありませんでした。

Last year, Tokyo (the Kanto region) experienced neither significant typhoon damage nor flooding, nor did it suffer heavy snowfall severe enough to require the deployment of the Self-Defense Forces, which could potentially determine residents' survival.

(まあ、酷暑災害はありましたが、これは日本人全員が被害者でしたから)

(There was, of course, extreme heat, but in that case, all Japanese were victims.)

―― 絶対、どこかで、この負債を支払わなければならない

と、私は怯えています。

And yet, I fear this debt will inevitably have to be paid somewhere, someday.

とはいえ、統計を取り扱うエンジニアとしては、これはおよそ合理的とは思えない感情でもあります(「ギャンブラーの誤謬」という用語で検索してみて下さい)。

That said, as an engineer who works with statistics, I recognize that this feeling is hardly rational (see the term "gambler's fallacy").

その不安のトップにあるのが「大地震」で、その次には「富士山の噴火」です。もちろん、洪水などの水害はデフォルトです。以前もお話ししましたが、東京の河川付近一帯は、例外なくハザードマップ上で"真っ赤"です。

At the top of my list of anxieties is a significant earthquake, followed by a possible eruption of Mount Fuji. Flood-related disasters are, of course, a given. As I have mentioned before, areas along Tokyo's rivers are, without exception, marked in deep red on hazard maps.

天災に弱すぎる――具体的には、たった1cmの積雪で、当日はもちろん、その後数日間は交通混乱が避けられないほど、この街は懦弱です。

This city is far too vulnerable to natural disasters, so much so that even a mere one centimeter of snowfall can cause traffic chaos not only on that day, but for several days afterward.

---

何かのコラムで読みましたが――

I once read in a column

最近の豪雪災害のニュースを見ていると、「東北の人々は、この被害だけで、その土地を捨てて逃げようとは思わないのか?」と、つい考えてしまいます。しかし一方で、東北の人々は、「東京に住んでいる人は、あんな災害に弱い街に住んでいるのか?」と思っているようです。

When watching recent news about heavy snowfall disasters, I find myself wondering, "Don't people in Tohoku ever consider abandoning their land and fleeing after experiencing such damage?" Yet at the same time, it seems that people in Tohoku think, "People in Tokyo live in a city that is that vulnerable to disasters?"

一回の大地震で、数万人から十数万人の死者が想定されている街――それにもかかわらず、なぜこんな街の地価が上昇するのか、不思議に感じることがあります。

This is a city where a single major earthquake is expected to result in tens or even hundreds of thousands of deaths, and yet, I cannot help but find it puzzling that land prices continue to rise.

加えて言えば、東京は間違いなく外国からミサイルロックオンされている街です(多分、同盟国でさえロックしていると思います)。軍事力の意思決定拠点(行政、国会、自衛隊の司令部)が集約している街でもあります。我が国(の軍事力……もとい、防衛力)を無力化するなら、ここを一撃するのが最も手っ取り早いことは、私にでも分かります。

In addition, Tokyo is undoubtedly a city targeted by foreign missile locks (probably even by allied nations). It is a city where centers of military decision-making, administrative bodies, the National Diet, and the headquarters of the Self-Defense Forces are concentrated. If one wanted to neutralize our country's military power, pardon me, defense capability, it is obvious even to me that striking here would be the quickest way.

---

この矛盾を「経済合理性」で説明しようとすると、たいてい話は破綻します。

When one tries to explain this contradiction in terms of economic rationality, the argument usually falls apart.

期待値で見れば、明らかに割に合いません。被害確率は低いものの、発生時の損失が巨大すぎるからです。

From an expected-value perspective, it clearly does not pay off. Although the probability of damage is low, the losses incurred if it occurs are too significant.

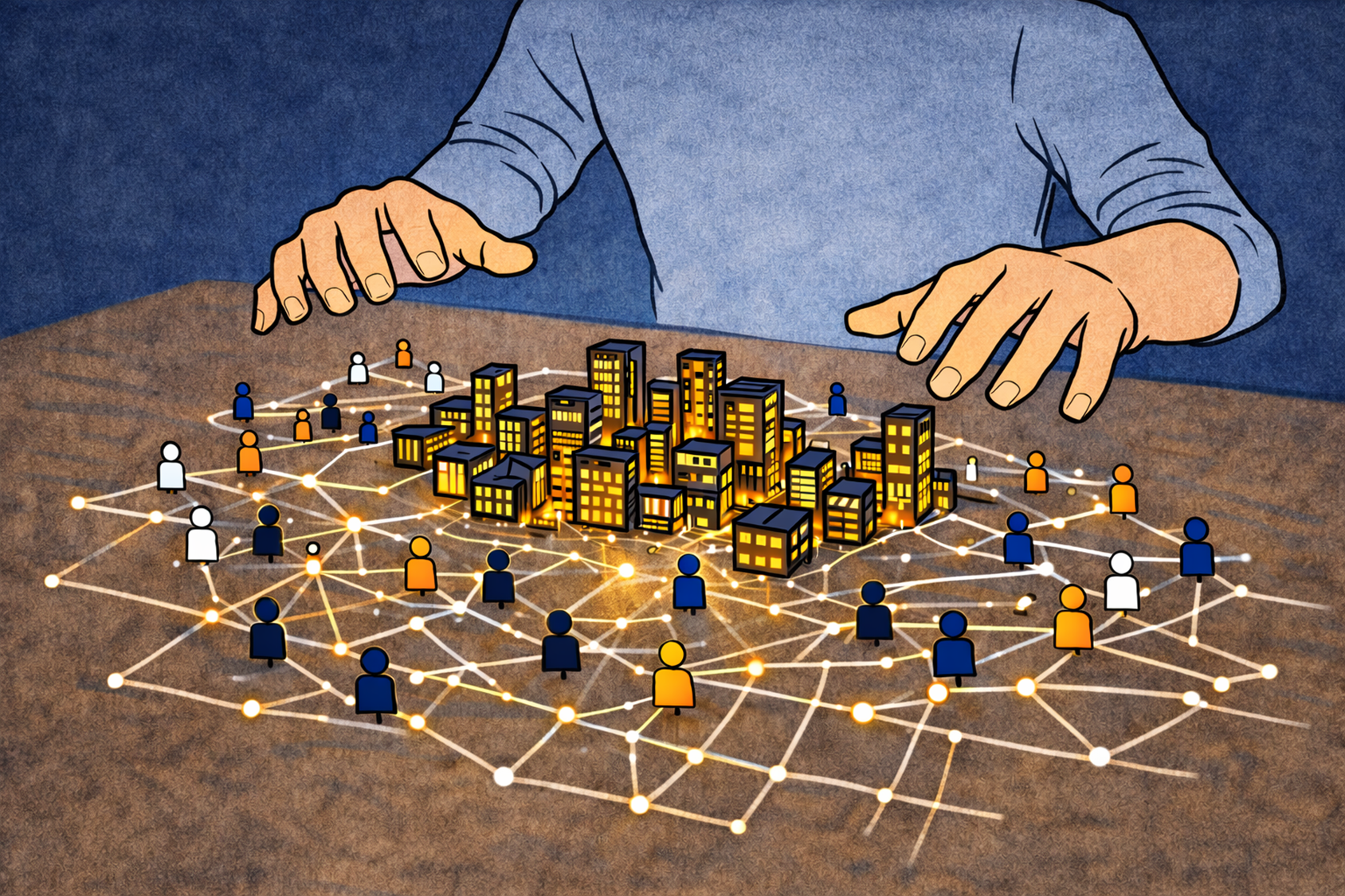

それでも人は集まり、地価は上がり、インフラはさらに集約されています。

Yet people continue to gather, land prices rise, and infrastructure becomes even more concentrated.

渋谷駅の鉄道インフラ大改造(キャッチコピーは「100年に1度の大改修」)を扱ったNHK特集は大変面白かったのですが、私は――「渋谷の街が、大地震と大火災で灰燼に帰した後で、やればいいじゃないか」と思ってしまいました。

An NHK special on the massive redevelopment of Shibuya Station's rail infrastructure (branded as "the once-in-a-century renovation") was fascinating. Still, I found myself thinking, "Why not just do it after Shibuya has been reduced to ashes by a major earthquake and fire?"

おそらく、私と同じように考える人(特に幹部クラスの年配者たち)は、そこそこ多かったのではないかと思います。それでもこの大改造を敢行した中堅管理職(?)の政治力と、それを実行した技術者たちの実行力の方に、私はむしろ感心してしまったのです。

I suspect many people shared my view, especially older executives. Even so, I found myself more impressed by the political clout of the mid-level managers who pushed this project through, and by the execution capability of the engineers who carried it out.

閑話休題。

Now, to return to the main topic.

---

通勤が楽であること、仕事があること、病院が近いこと、文化が集中していること。これらは毎日効いてくる効用です。一方で、地震や噴火は「まだ起きていない」未来の話です。

Ease of commuting, job availability, proximity to hospitals, and cultural concentration are benefits that affect every day. Earthquakes and eruptions, on the other hand, are future events that "have not yet happened."

こうして、「日常の利便性」が「非日常の破局」を塗り潰していきます。

In this way, the convenience of everyday life paints over the prospect of extraordinary catastrophe.

人間は、確率よりも体感を重視する生き物です。毎日感じる快適さは、年に一度も感じない不安より、はるかに強く作用します。

Human beings prioritize lived experience over probability. Comfort felt every day exerts a far stronger influence than anxieties felt less than once a year.

だからこそ、東京は「合理的に危険な都市」でありながら、「感情的に正解な都市」であり続けてしまいます。この二重構造が、都市の脆さを覆い隠しているのです。

That is why Tokyo remains a city that is rationally dangerous yet emotionally correct. This dual structure conceals the city's fragility.

さらに言えば、東京という街は「逃げにくい」構造を、自ら作り続けています。

Furthermore, Tokyo continues to develop a structure that impedes escape.

住宅価格の高騰は住民の可動性を奪い、職の集中は代替地を消し、インフラの巨大化は撤退コストを引き上げます。

Rising housing prices strip residents of mobility, job concentration eliminates alternatives, and massive infrastructure investments increase the cost of withdrawal.

その結果、「危ないと分かっていても離れられない」という、静かなロックインが進行します。

As a result, a quiet lock-in ensues, in which people understand the danger yet cannot leave.

災害に強い街とは、単に堤防が高い街ではありません。住民が「動ける」街です。一時的にでも離脱でき、別の場所で生活を継続できる余地がある街です。

A disaster-resilient city is not simply one with high levees. Is it a city where residents can move to a town that allows temporary evacuation and the possibility of continuing life elsewhere?

以前、私は自分の町内の地図を俯瞰してみたことがありますが、そのとき正直、青冷めました。町内からの脱出ルートが4本しかなく、そのうち2本は地震で寸断される可能性が高いと感じたからです。

Once, when I looked down at a map of my neighborhood from above, I honestly turned pale. There were only four evacuation routes out of the area, and I felt that two of them were highly likely to be cut off in an earthquake.

---

ともあれ、「絶対、どこかで、この負債を支払わなければならない」とは思っていますが――

In any case, I do believe that this debt will inevitably have to be paid somewhere, someday.

その支払いは、「私がいなくなった後がいいな」とも思っています。

But I also hope the payment will come after I am gone.

逃げきれるか、どうか。「自然災害 vs 私の寿命」を、ChatGPTに計算してもらいました。

I asked ChatGPT to calculate whether I can escape "natural disasters versus my remaining lifespan."

まあ、その計算結果を本気にしているわけではありません。ただの、ちょっとした気休めです。

I am not taking the result seriously, of course. It is merely a small source of comfort.

====== ChatGPTによるフェルミ推定結果 ======

自身が"致命的または生活継続不能級"の直撃を受ける(死亡、または長期避難・資産喪失・就労不能などで生活が崩壊)と定義します。「あなたが先に勝つ」は、**それが起きる前に寿命が先に尽きる(あるいは直撃を受けずに過ごせる)**です。

1) 残り寿命(ざっくり)

60歳からの残り寿命は、フェルミでは 25年(85歳) を基準に置きます。(20年-30年の幅でも後で感度を出します。)

2) 年あたりの「直撃(生活崩壊級)」確率 p を置く

ここが肝です。

「首都圏で大きい地震が起きる確率」ではなく、あなたの生活が"壊れるレベル"で当たる確率なので、年あたり 0.5%-2% くらいのレンジを置くのがフェルミとして妥当だと思います。

0.5%/年:大災害は起きても「自分は致命傷を外す」寄り(耐震・立地・運)

1%/年:そこそこ現実的な中庸

2%/年:地震・水害・猛暑・広域ライフライン断などを広めに取り、「生活崩壊」判定も厳しめ

3) 生涯(残り25年)で直撃する確率

独立近似で、累積確率は

P(直撃)=1 (p)^N(N=25年)です。

p=0.5% → 0.995^25 ≒ 0.882 ≒ 11.8%

p=1% → 0.99^25 ≒ 0.778 ≒ 22.2%

p=2% → 0.98^25 ≒ 0.603 ≒ 39.7%

よって「あなたが勝つ(直撃を食らわずに寿命が先に来る)」確率は P(直撃) なので、

楽観(p=0.5%):約88%

中庸(p=1%):約78%

厳しめ(p=2%):約60%

4) 感度(残り寿命が20年/30年なら)

p=1%で見ると、

N=20年:0.99^20 ≒ 18.2% → 勝率 約82%

N=30年:0.99^30 ≒ 26.0% → 勝率 約74%

つまり、このゲームは寿命よりも p(年あたり直撃率)をどう置くかで結果が大きく動きます。

結論(フェルミ)

あなたが60歳で東京(関東)に住み続ける前提なら、自然災害 vs あなたの寿命 の勝率(あなたが勝つ)は、ざっくり 60-90%、中庸で約75-80% という見積もりになります。

この勝率を上げる"現実的なレバー"は、地震そのものの確率を議論するより、「直撃(生活崩壊級)」の p を下げる方向です。耐震等級、ハザード(浸水・土砂)からの距離、高層エレベータ依存の低減、備蓄、家族の集合手順、職住の冗長化、このあたりが全部 p に効きます。

====== ChatGPTによるフェルミ推定結果 ここまで ======