研究員だけでなく、たぶん多くの人が悩んでいると思うのですが、報告書などに対する上司のレビューで、こういうものがあります。

Not only researchers but probably many people struggle with this: when a supervisor reviews a report, there is a comment like this.

―― なんとなく分からん。

"I somehow don't get it."

多いです。というか、ほとんどこれです。

It happens often. In fact, it is almost always this.

そこでこちらが「どう直せばいいんでしょうか」と聞くと、「自分で考えて下さい」と言われる。

So when we ask, "How should I fix it?", we are told, "Please think about it yourself."

エンジニアの方なら分かると思いますが、「何が悪いのか分からないレビュー」というのは、かなりのダメージを受けます。

Engineers will understand this, but a review that does not explain what is wrong is extremely destructive.

バグなら楽です。「ここが壊れている」と言われれば直せます。設計でも同じで、「この構造では要件を満たせない」と言われれば作り直せます。

Bugs are easy. If someone says, "This part is broken," you can fix it. The same applies to design: if you are told "This structure cannot satisfy the requirements," you can redesign it.

しかし「なんとなく分からん」というレビューは、コンピュータで言えば仕様未定義エラーです。

However, a review saying "I somehow don't get it" is like an undefined-specification error in computing.

この指示では対策が取れません。無限の解空間の中の一つの解ベクトルが否定されただけのことだからです。

With such an instruction, there is no way to respond. It simply means that one vector in an infinite solution space has been rejected.

つまりこれは、「残りの無限数のベクトルを全部試せ」と言われているようなものです。

In other words, it is like being told, "Try all the remaining infinite vectors."

---

ただ、この話はエンジニアだけの問題ではないと思うのです。

However, I do not think this issue is limited to engineers.

私も被害者面だけをするつもりはありません。私だって、ちゃんと加害者やってきました。

I do not intend to play only the victim. I have also been a perpetrator.

皆さんも同じではないでしょうか。

I suspect many of you have done the same.

例えば創作作品に対して、「なんかこの映画、面白くなかった」「この本、評判ほど良くない」「この作品、何が言いたいのか分からん」などと言うことがあります。

For example, when it comes to creative works, we often say things like "That movie wasn't very interesting," "This book isn't as good as its reputation," or "I don't get what this work is trying to say."

理由も説明せず、改善点も1mmも示さない。それでもなぜか、こういうものが「批評」というジャンルとして成立しています。

We explain no reasons and suggest not even a millimeter of improvement. Yet somehow this still counts as a genre called "criticism."

私、思うんですが、人間の最もプリミティブな殺意って、実は「なんとなく分からん」から始まっているんじゃないでしょうか。

I sometimes think that the most primitive murderous impulse in humans actually begins with "I somehow don't get it."

---

さて、作業者や創作者側の視点から言えば、結論はシンプルです。

Now, from the perspective of workers or creators, the conclusion is simple.

「お前(レビューア)の頭が悪い」。

"The reviewer is simply stupid."

これです。この結論は、作業者や創作者に最も寄り添った、そして最も優しくて単純明快な回答です。

That's it. This conclusion is the most sympathetic to workers and creators, and the simplest and most comforting answer.

ただ、これだけでは世の中に溢れている「なんとなく分からん」というレビューに対応できません。ですので、レビューア側の視点からも少し考えてみます。

However, this alone does not help us address the flood of "I somehow don't get it" reviews worldwide. So let us also consider the reviewer's perspective.

レビューアが「なんとなく分からん」と感じる理由は、大体次のようなものです。

The reasons reviewers feel "I somehow don't get it" are roughly as follows.

(1)作者の頭の中ではつながっている論理が、文章や作品として十分に伝わっていない。

(1) The logic that is connected in the author's mind has not been sufficiently conveyed in the text or the work.

(2)作者の中では自然につながっている論理のジャンプに、読者が追いつけない。

(2) The reader cannot follow the logical jumps that feel natural to the author.

(3)全体構造が見えない。

(3) The overall structure is not visible.

(4)ロジック整理を読者に丸投げしている。

(4) The organization of logic is thrown entirely onto the reader.

(5)作者自身が評価基準を言語化できていない。

(5) The author has not verbalized their own evaluation criteria.

これを簡単に言うと「読みづらい」「論理が飛んでいる」「何かがおかしい」となるわけです。

In short, it means "hard to read," "logic jumps," or "something feels wrong."

---

ただ、この問題の原因は、実はかなり単純だったりします(正直、そう思いたくはないのですが)。

However, the cause of this problem is actually quite simple (though honestly, I would rather not admit it).

原因は、作者が作者の世界観の"内側"で作品を作っているからです。

The reason is that the author creates the work from within their own worldview.

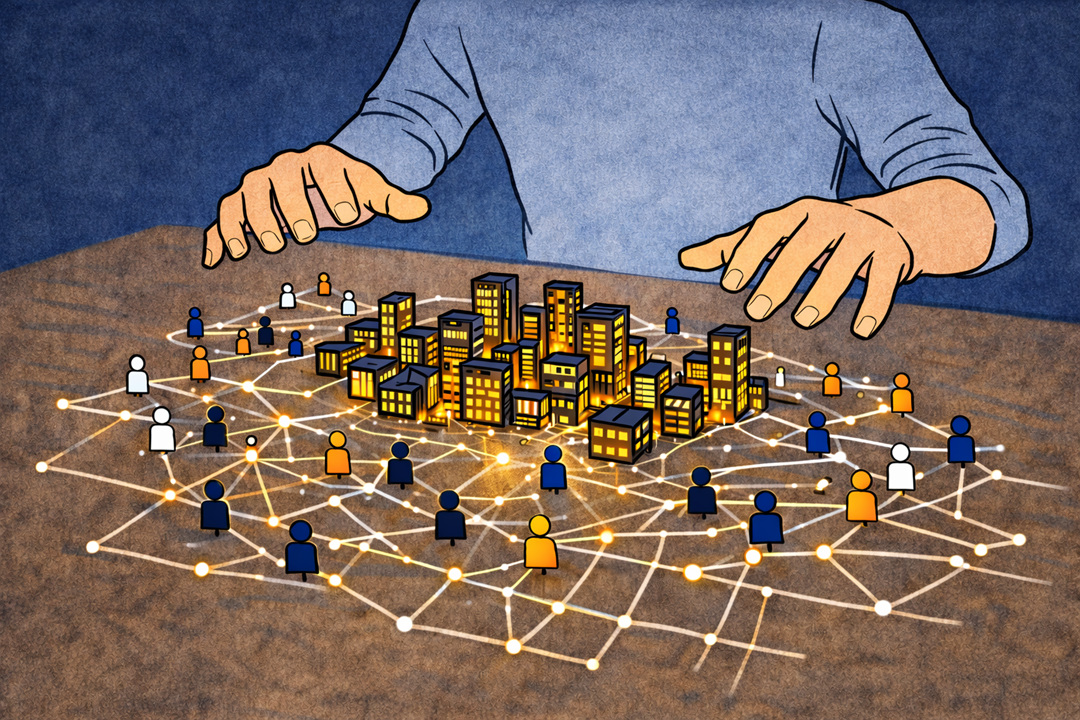

例えば「異世界小説」を考えてみましょう。

For example, consider an isekai (other-world fantasy) novel.

作者の頭の中では、すでに世界が完成しています。

In the author's mind, the world is already complete.

『魔法は日常的な技術で、王国と帝国は長年戦争していて、空に浮かぶ島は古代文明の遺産』

"Magic is an everyday technology, the kingdom and the empire have been at war for years, and the floating islands are relics of an ancient civilization."

こういう設定がすべて共有されている。

All these assumptions are already shared in the author's mind.

だから作者は、「王国の魔導兵が浮遊島から攻撃を開始した」と普通に書けてしまう。

Therefore, the author can casually write, "The kingdom's magic soldiers began their attack from the floating island."

しかし読者にとっては、『なぜ島が浮いているのか、魔導兵とは何なのか、なぜ戦争しているのか』、何一つ分かりません。

But for the reader, nothing is clear: why the island floats, what magic soldiers are, or why there is a war.

作者の頭の中では整合している世界でも、読者から見れば「状況がよく分からない物語」です。

Even if the world is internally consistent in the author's mind, for the reader it becomes "a story whose situation is unclear."

つまり物語を書くには、物語だけでは足りません。その世界そのものを説明しなければならない。

In other words, writing the story itself is not enough; the world itself must be explained.

定量的に言えば、作品が1なら世界説明は100とか1000必要になる ―― これは、かなり地獄です。

Quantitatively speaking, if the story is "1," does the explanation of the world become "100" or "1000"? which is quite hellish.

---

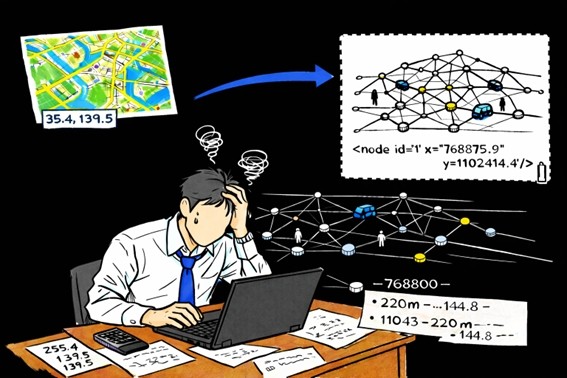

そしてこの構造は、研究員の報告書でも全く同じです。

And this structure is exactly the same in research reports.

研究者の頭の中には、『研究背景、問題設定、既存研究、使用データ、分析手法、評価指標』がすでに整理されています。

In the researcher's mind, the research background, problem definition, prior studies, data used, analytical methods, and evaluation metrics are already organized.

ですから「本手法により接触機会の増加が確認された」と書けば済むような気がしてしまう。

So it feels sufficient to simply write, "This method confirmed an increase in contact opportunities."

しかし読む側からすると、『接触機会とは何なのか、何と比較しているのか、どの計算方法なのか、どのデータなのか』が分かりません。

However, from the reader's perspective, it is unclear what "contact opportunity" means, what it is compared with, how it is calculated, and what data it is based on.

研究者の頭の中の世界が、読者の頭の中にインストールされていないからです。

That is because the world inside the researcher's mind has not been installed inside the reader's mind.

つまりここでも、研究成果が1なら背景説明は100とか1000になる。

So here as well, if the research result is "1," the background explanation becomes "100" or "1000."

そして、この説明を省略したときに発生するレビューが、「なんとなく分からん」です。

And when that explanation is omitted, the resulting review becomes "I somehow don't get it."

---

私は、今、この「なんとなく分からん」というコメントを受けて、心底キレている最中です。

Right now, I am genuinely furious after receiving this "I somehow don't get it" comment.

ですので、こういうコラムを書いて自分自身を落ち着かせています。

So I write columns like this to calm myself down.

気分としては『写経』です。書いているものがお経ではないだけの、精神安定行為です。

It feels like copying sutras. The only difference is that what I am writing is not a Buddhist scripture; it is merely a form of mental stabilization.

私も、一応、大人なので「作者の説明が足りないのだ」と理解はしています。

I am, after all, an adult, so I understand that the author's explanation may be insufficient.

理解はしているのですが――それでも、私は『私の説明が足りないのではなく、世界の理解力が足りない』と考えたい。

I do understand that, but still, I would rather believe that it is not my explanation that is lacking, but the world's ability to understand.

---

この世の中は私のために存在しているのだから、本来ならば私の世界観を世界の方が理解すべきであり、努力が足りないのは私以外の全人類です。

Since the world exists for my sake, it is only natural that it should understand my worldview; therefore, those who lack effort are all humans other than myself.

という訳で、私の結論はいつもの通りです。

So, as always, my conclusion is the same.

―― 私は正しい。世界が間違っている

"I am right. The world simply does not try hard enough to understand me."