タイでは、お坊さんが町を歩いていると、人々が道を開け、色々な順番の前に並ぶことを勧められるという話を聞いたことがあります。

In Thailand, I have heard that when a monk walks through town, people open a path for him and even invite him to go ahead of them in various queues.

ちょっと調べてみました。

So I looked into it a little.

---

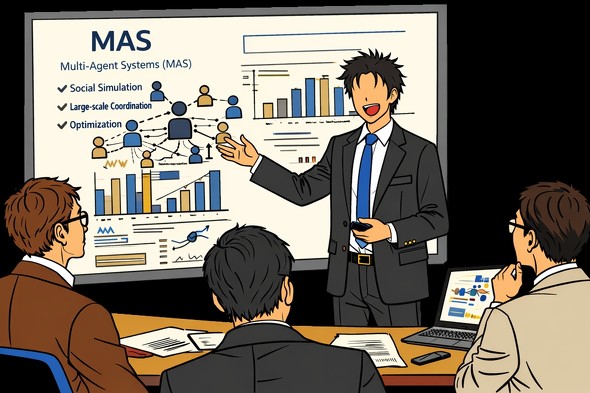

タイでは仏教(上座部仏教)が社会の中心的な宗教であり、僧侶は社会的に非常に高い敬意を受ける存在です。

In Thailand, Buddhism (Theravada Buddhism) is the central religion, and monks are figures of great respect.

そのため、日常生活の中で一般の人より優先されたり、特別扱いされる慣習がいくつかあります。

For that reason, there are several customs in daily life where monks are given priority or special treatment over ordinary people.

多くのタイ人は、僧侶を見かけると自然に道を譲ります。

Many Thai people naturally give way when they see a monk.

- 行列(切符売り場、レジなど)では前に譲る

- In queues (ticket counters, cash registers, etc.), people let them go ahead.

- エレベーターや入口でも優先される

- They are given priority at elevators and entrances as well.

- 混雑した場所では周囲が道を開ける

- In crowded places, people around them open a path.

公共交通ではかなり明確な扱いがあります。

Public transportation also treats monks quite explicitly.

- バスや電車に『僧侶専用席』がある

- Buses and trains have "monk-only seats."

- 席が空いていなくても一般客が席を譲る

- Even if no seats are available, ordinary passengers give up their seats.

- 女性は僧侶に直接触れてはいけないため、物の受け渡しを避ける配慮がある(この背景は、良く分かりませでした)

- Women should not touch monks directly, so care is taken to avoid direct hand-to-hand exchanges of items (I do not fully understand the background of this).

僧侶は社会的にも一定の優遇があります。僧侶個人は所得税を払う必要がありません(寄進は課税対象外)。また、兵役は免除されます。

Monks also receive certain social privileges. Individual monks do not need to pay income tax (donations are not subject to taxation), and they are exempt from military service.

僧侶への侮辱は社会的に強く非難されます。 王室と並び、宗教は国家アイデンティティの重要要素だからです。

Insulting monks is strongly condemned socially, because religion—along with the monarchy—is an important element of national identity.

また、僧侶は、社会文化的な尊敬を受ける対象でもあります。

Monks are also objects of social and cultural respect.

- 僧侶より「頭を高くしないようにする」

- One should not hold their head higher than a monk.

- 座る時は僧侶より低く座る

- When sitting, one sits lower than the monk.

- 合掌して挨拶する

- People greet them with hands pressed together.

ただし、ただし最近は少し状況が変わってきていて、僧侶のスキャンダル(高級車、金銭問題など)、若者の宗教離れ、都市部での慣習の弱まりなどがあり、『地方では強く、都市ではやや弱い』という傾向があります。

However, recently the situation has changed somewhat, with scandals involving monks (luxury cars, financial issues, etc.), younger generations drifting away from religion, and weakening customs in urban areas. As a result, the tradition remains strong in rural areas but somewhat weaker in cities.

---

僧侶は立派な職業かもしれませんが、私は、僧侶よりもっと凄い、そして尊敬されうる、そして人類社会の根幹を支える仕事をしている人を知っています。

Being a monk may be a respectable vocation. Still, I know people who do something even more remarkable, something deserving of even greater respect, and something that supports the very foundation of human society.

出産・育児・保育に関わっている方々です。

They are people involved in childbirth, childcare, and childcare support.

大きいお腹をしながら働いている女性、子どもをベビーカーで運んでいる子どもを連れている保護者(お母さんも、お父さんも)、そして保育に関わっているすべての人は、『タイの僧侶と同程度の、社会的保護と、社会的敬意』を得られるべきではないかと思うのです。

Women working while carrying large pregnancies, parents pushing children in strollers (both mothers and fathers), and everyone involved in childcare—these people, I believe, deserve the same level of social protection and respect as monks in Thailand.

子どもを育てるという行為は、個人の家庭の問題ではなく、社会の持続そのものに直結する行為です。

Raising children is not merely a private family matter; it is directly connected to the sustainability of society itself.

にもかかわらず、日本では、子どもを連れている人が、電車の中で肩身の狭い思いをしていたり、ベビーカーが邪魔者扱いされていたりする光景を、私は時々見かけます。

Yet in Japan, I sometimes see people with children feeling uncomfortable in trains, or strollers being treated as nuisances.

私は、こういう人に対して心底、『何考えているんだ』と疑問になります。

When I see such reactions, I honestly find myself wondering, "What on earth are they thinking?"

もちろん、日本でも席を譲る人はいますし、子どもに優しい人はたくさんいます。

Of course, there are people in Japan who give up their seats, and many who are kind to children.

しかしそれは、あくまで個人の善意に依存したものであって、社会の「文化」や「行動規範」として定着しているとは言い難いように思えます。

However, that seems to rely merely on individual goodwill, and it is difficult to say that it has become firmly established as a social "culture" or "norm of behavior."

---

タイでは、僧侶に道を譲ることは「親切な行為」というよりも、「当たり前の行動」です。

In Thailand, giving way to monks is not considered an act of kindness but simply normal behavior.

それは個人の善意ではなく、社会が共有している価値観として成立しています。

It is not based on personal goodwill but on values shared by society.

つまり、その社会が「誰を尊重するのか」を決めると、人々の行動様式は自然と変わるのです。

In other words, when a society decides whom it respects, people's behavior naturally changes.

もし、日本の社会が本当に「子どもは社会の宝である」と考えているのであれば、子どもを連れている人に対する社会的な扱いは、自ずから決まってくるはずです。

If Japanese society truly believes that "children are society's treasure," then the way people treat those raising children should naturally follow from that belief.

しかし、現実の日本社会を見ていると、どうも私には「宝の扱い」には見えない。

However, when I look at Japanese society as it actually is, it does not quite look to me like we are treating them as treasures.

YouTubeなどで、日本の礼儀、作法、丁寧、親切を日本人が称える「日本バンザイコンテンツ」を、私は不快な気分で見ています。

On YouTube and elsewhere, I often see "Japan-praise content" where Japanese people celebrate Japan's politeness, manners, and kindness, and I watch it with a sense of discomfort.

これは、多分、足元の『出産・育児・保育に関わっている方々に対する敬意を示せない国民ごときが、何いっていやがる』と思っているからだと思うのです。

I suspect that is because I find myself thinking, "People who cannot even show proper respect to those involved in childbirth and childcare have no business boasting about such things."

---

で、私が思うのは、出産・育児・保育に関わっている方々に対する対応は、この「タイの僧侶」をケーススタディとする社会基盤の再構築(リストラクション) ―― というか、丸パクリで良いと思うんですよ。

So what I am thinking is that the way society treats people involved in childbirth, childcare, and early education could be rebuilt using "Thai monks" as a case study for reconstructing social infrastructure—or, frankly, we could copy it outright.

例えば、日本が本気で「子どもは社会の宝だ」と言うのであれば、私はタイの僧侶の扱いを、そのまま丸ごとコピーしても良いと思っています。

For example, if Japan truly means it when it says that "children are society's treasure," then I believe we could copy the way Thai society treats monks.

■ 駅や空港では、妊婦や乳幼児を連れた保護者のための専用レーンを作る。そこでは一般の人は並べない。並んでいたとしても、妊婦やベビーカーが来たら、全員が一歩下がって道を開ける。

- At train stations and airports, create dedicated lanes for pregnant women and parents with infants. Ordinary people would not line up there, and even if they were already standing there, they would step aside and make way for a pregnant woman or a stroller.

■ 電車には「子育て車両」を作る。その車両では、ベビーカーは畳む必要もないし、子どもが泣いても誰も文句を言わない。むしろ、周囲の乗客が「あやすのを手伝う」くらいの空気が普通になる。

- On trains, create "child-raising cars." In those cars, strollers would not need to be folded, and no one would complain if a child cried. In fact, it would become normal for surrounding passengers to help soothe the child.

■ レジの行列でも同じです。ベビーカーや小さな子どもを連れている人が来たら、列の前の人が自然に場所を譲る。これは「親切」ではなく、単なる社会の作法です。

- The same would apply at checkout lines. If someone with a stroller or a small child arrives, the person at the front of the line naturally lets them go ahead. This would not be considered kindness, but simply social etiquette.

■ レストランでも、役所でも、病院でも、窓口でも同じです。「子ども連れ優先」という表示があり、誰もそれに文句を言わない。

- The same principle would apply at restaurants, government offices, hospitals, and service counters. Signs would indicate "priority for people with children," and no one would complain.

そして、もう一歩踏み込んでも良いと思います。

And we could go one step further.

■ 妊婦や乳幼児を連れている保護者は、公共交通機関の料金を無料にする。

- Make public transportation free for pregnant women and parents with infants.

■ 子どもを二人以上育てている家庭には、所得税の大幅減免を与える。

- Give major income tax reductions to families raising two or more children.

■ 保育士には国家資格としての社会的地位と高待遇を与え、給与は公務員の上位水準にする。

- Grant childcare workers national professional status and high待遇, with salaries at the upper level of public servants.

そして、子どもを連れている人に対して露骨に迷惑そうな態度を取る人間がいた場合、私はこういう文化を作ってもいいと思っています。

And if someone openly shows annoyance toward a person with children, I think it would be acceptable to create a culture like this:

■ 周囲の人が、その人を静かに睨む。

- The people around them quietly glare at that person.

つまり、「それは社会として恥ずかしい行動だ」という空気を共有するのです。

In other words, people share an atmosphere that says, "That behavior is shameful for our society."

---

タイでは、僧侶に対して失礼な態度を取る人間は、法律よりも先に、社会の空気によって制裁されます。

In Thailand, someone who behaves disrespectfully toward a monk is sanctioned first by social atmosphere, even before any legal mechanisms.

法制に意味がないとは言いませんが、私は、このような社会を、我が国特有のシステムである" 空気" または" 同調圧力" で実現したい。

I am not saying laws are meaningless, but I would like to realize such a society through Japan's unique systems of "atmosphere" and "social pressure."

というか、" 空気" と" 同調圧力" は、我が国のお家芸でですよね?

After all, "reading the air" and "conformity pressure" are something of a national specialty in Japan, aren't they?

ここで、この悪名高き国民性を活用しない手はないと思うんですよ。

So it would be a waste not to make use of this infamous social mechanism.

あとは、その実現方式ですね。

What remains is figuring out how to implement it.

私は、私が培ってきた" 心理学" と" 移動行動" のシステム化から、この課題にアプローチしてみます。

I will try to approach this issue from the systemization of psychology and human mobility behavior that I have developed.

皆さんは、皆さんのやりかたでのアプローチを考えてみて下さい。

Please consider your own approaches as well.

---

私には引け目があります。

I have a certain sense of guilt.

娘たちの育児に、今、私がここで書いているほどのことができていたか、と問われれば、

If I were asked whether I actually did the things I am writing about here when raising my daughters,

―― 全然ダメダメだっただろ。

"I would have to say I was completely inadequate."

と、2秒で断定できるくらいです。

I could conclude that in about two seconds.

ですから、私はこの文章の内容を、あまり声高に主張できる資格がないのです。

Therefore, I do not really have the qualifications to insist loudly on the ideas in this essay.

そこで私は考えました。

So I started thinking.

人間には、人生のセカンドラウンドにおける称号(タイトル)の取得です。" 博士号" ならぬ、" 祖父号" の取得です。

Human beings have the chance to obtain a title in the second round of life. Not a PhD, but a "Grandfather Degree."

もちろん大学は、この資格を発行してくれませんし、タイトル付与者となるであろう娘たちも、簡単には発行してくれないでしょう。

Of course, universities will not issue such a qualification, and my daughters—who would probably be the ones awarding the title—will not grant it easily either.

しかし、もし将来、孫ができたときに、ベビーカーを押している人を見かけたら自然に道を開ける人間でありたいし、子どもが電車で泣いていても「よし、もっと元気に泣き叫べ」と思える人間でありたいと思っています。

However, if I someday have grandchildren, I would like to be the kind of person who naturally makes way when seeing someone pushing a stroller, and who thinks, "Good, cry louder and stronger," when a child cries on a train.

少なくとも、そのときには、「子どもは社会の宝です」という言葉を、ポスターではなく、自分の行動で言える人間でありたいと思っています。

At the very least, I would like to be someone who can say "children are society's treasure," not through posters, but through my own actions.

まあ、その前にまず、娘たちから「あなたに祖父号を授与します」という認定を受けなければならないのですが ――

But before that, I first need to receive certification from my daughters, saying, "We grant you the Grandfather Degree."

これが、どうも、私の博士号より、取得難易度が高そうな気がしています。

And somehow, it feels like this one may be harder to obtain than my PhD.

それは、私が、子ども一人ひとりを「3億円の札束のかたまり」として見るようにしているからです。で、お伺いしますが、今のあなたに「3億円」の価値、ありますか?